Your Superpower For Building Better Meetings

Like much of a manager’s efforts, setting meeting agendas is “work about the work.” And to put it another way (borrowing the words usually attributed to Edwin Schlossberg about effective writing) it’s also “creating the context in which other people can think.”

Let that sink in: Creating the context in which other people can think.

That’s incredibly powerful. It’s almost like having a superpower.

And while the literal meeting agenda matters a great deal, your frame of mind as you construct that agenda matters even more. It can mean the difference between a productive and useful discussion that serves your team’s goals, and swift descent down well-worn ratholes.

David Rock is one of my favorite writers on workplace psychology, and in Quiet Leadership he shares a simple framework that I’ve used to guide many meetings (and during them to gut-check whether we’re still on the right track). Rock says in the context of any project or meeting there are five ways to think (and communicate) and the outcome depends a great deal on which one is dominant:

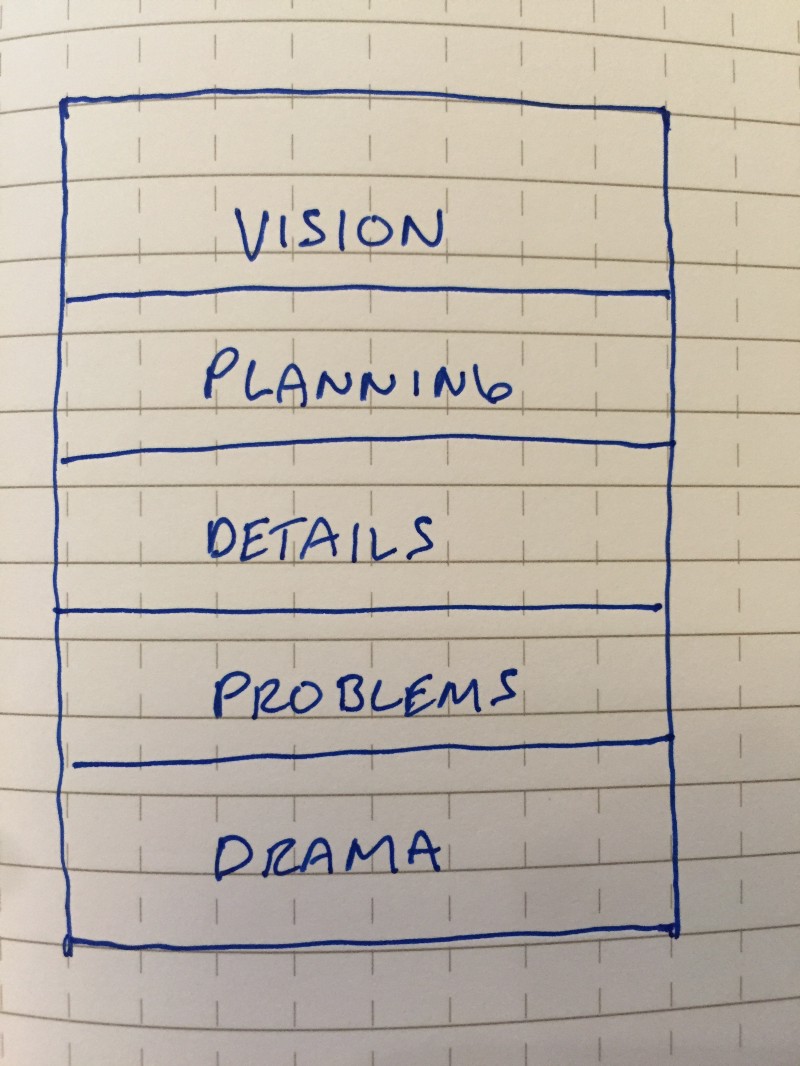

The five categories Rock describes are:

- Vision. The “why” or “what” stage of thinking at a high level of what you’re trying to accomplish and why.

- Planning. You’ve identified the objective, and now it’s time to think about how you’re going to get there.

- Details. Your goal is clear, you’ve charted a course, and this is about execution. As Rock points out, this is where most people naturally put their energy unless deliberately guided up the stack (or dragged down into one of the next two).

- Problems. Something is wrong and it’s time to work on fixing it. (There is no shortage of problems in any workplace, and this greedy beast will eat as much of your team’s attention as you let it.)

- Drama. Blame, fear, anxiety, and anger drive the emotionally charged discussions at this level. The least productive category of conversation (or thinking), yet a frequent endpoint of discussions that start with Problems.

Adding the time dimension

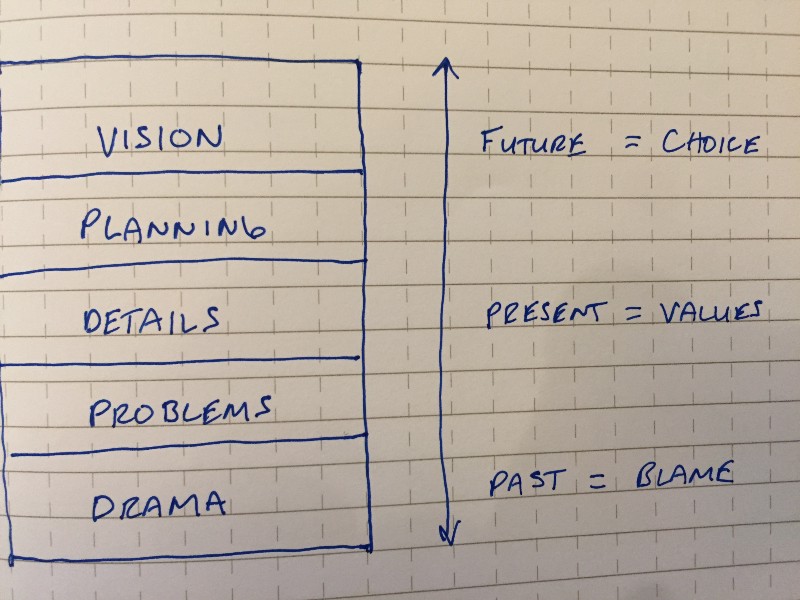

By itself Rock’s framework should be in your management toolkit. But I found that adding the dimension of time makes it even more useful.

In Thank You for Arguing, Jay Heinrichs (citing Aristotle) says all persuasion boils down to just three issues: Blame, Values, or Choice, and which one dominates depends a great deal on whether you’re discussing the Past, Present, or Future.

Overlaying that on Rock’s framework a few things become clearer:

- It’s obvious why most people gravitate toward Details. They’re here and now and right in front of us, and given how most of an organization is oriented toward short-term objectives, this makes sense.

- If you’re a leader, part of your job is spending a lot of time at the top of the stack, in the Vision category, making choices about the future. But that is not a natural place for most people, so you also have to make sure to get everyone else into the same context first, or you risk having others around the table approaching the discussion from a different level of the stack.

- Track your next few team meetings: Problems are inevitable, but if you’re spending a lot of time there, it suggests you need to step back and move up the stack — you’ve probably missed something along the way among the Vision, the Planning or the Details that is causing the Problem.

- Drama is both toxic and inevitable. We are human beings navigating complex social interactions, and it is neither possible nor desirable to exclude all of our emotions from our work. But with this framework you can spot when the meeting dips into Drama, acknowledge what’s happened, and swiftly return the discussion to a productive place.

- You might introduce this framework to your team, and keep it up on the whiteboard during an upcoming meeting: challenge your team to keep each other in the appropriate spot on the stack, whatever that may be for the discussion at hand (it can also be a great tool for helping team members productively call each other when they bring up “Drama” issues).

How do you apply this in practice? Imagine you’re leading a meeting to decide whether to move forward with a major 3-month project. The stakes are high, and there’s understandable anxiety around the room, which is manifesting in lots of incredibly detailed reasons why the project won’t or can’t work. You could try to counter each objection in turn, but doing so keeps the conversation firmly down in Detail/Problem land. Instead, bring the discussion back up by asking “What would have to be true 3 months from now for you to support this effort 100% right now?” You’ve returned the focus back to the future and brought everyone back to Vision and Planning where the discussion belongs.

Your job as a manager isn’t to do the work, it’s about creating and reinforcing the context in which the work is done, and the stack model above is a simple but powerful tool for setting the right context and agenda for your next meeting.