What Developers Do Now with AI, You’ll Do Next

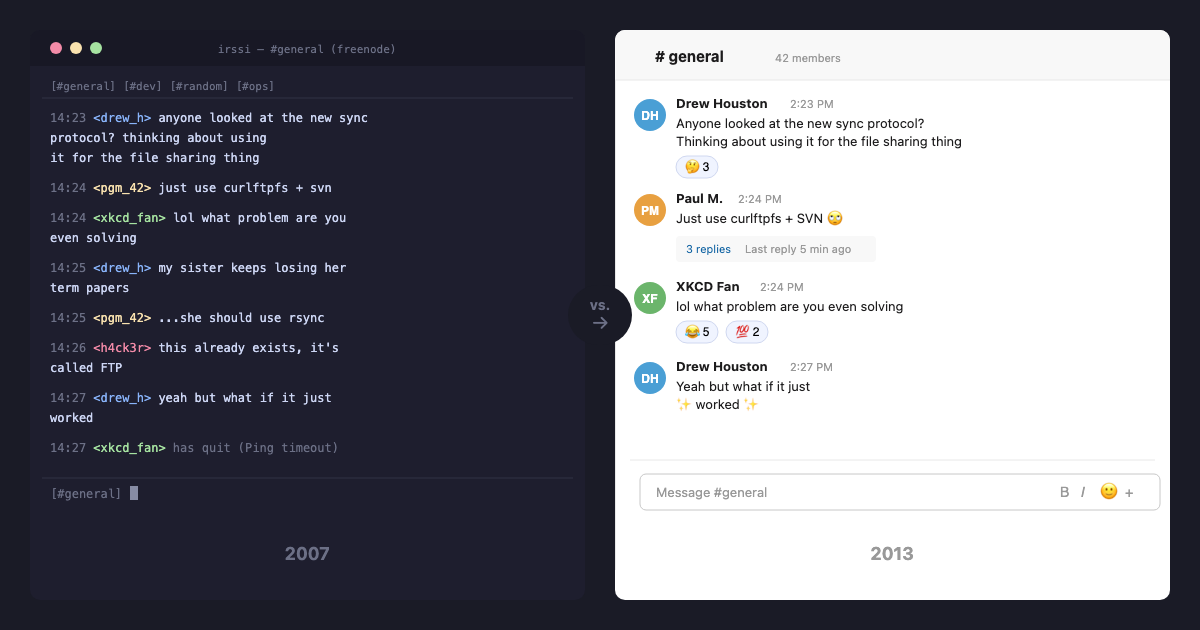

In April 2007, Drew Houston posted his Y Combinator application for a new product called Dropbox. He described it as “taking the best elements of subversion, trac and rsync and making them ‘just work’ for the average individual or team.” He knew exactly what he was building on — rsync, the command-line file synchronization tool that’s been shipping with Unix systems since 1996. Houston’s pitch was that his little sister could use Dropbox to keep track of her high school term papers without burning CDs or carrying USB sticks — and definitely without rsync.

A Hacker News commenter offered this feedback: you could already build such a system yourself “quite trivially” by getting an FTP account, mounting it locally with curlftpfs, and then using subversion or cvs.

That wasn’t wrong! The technology existed!

But the gap between “exists for people who know what curlftpfs means” and “works for a high schooler’s term papers” turned out to be worth about $12 billion.

Early reactions to Slack followed the same script: “it’s just IRC,” as if decades of chat protocol history made a more accessible tool’s wider potential redundant.

Indeed, for more than 30 years now, one of the best ways to see the future of knowledge work has been to watch how software developers work.

Their job may be to write software, but they tend to also write other software that makes it more efficient to write software. And then they write more software still, to help with all the other work that goes into writing software, like collaborating with colleagues or managing schedules and plans.

And it’s those broader tools — the ones applicable to other kinds of knowledge work — that offer the best preview of the future for the rest of us. Even when the future looks, at first, like something only a developer could love.

But for those willing to spend effort learning how developer tools work before they cross that gap to mainstream, there is competitive advantage.

I experienced this firsthand 20 years ago at O’Reilly Media, where I helped build an industry-leading publishing toolchain based on the observation that much of a developer’s workflow is around writing, editing, and collaborating on collections of complex, long-form text documents. It turns out that what works for a “codebase” works exceptionally well for a “book” too (especially if that book’s authors happen to also be software developers!)

That lesson has stuck with me throughout my career: pay attention to the tools that software developers are using, because with a bit of work they can often be incredibly powerful when applied to other kinds of knowledge work.

Same tune, new (AI) instrument

Over the past few months, I’ve noticed many of the smartest engineers I know all talking more and more about how transformative their work was becoming with Claude Code (and similar LLM tools).

And I kept hearing one specific theme over and over — that the work had shifted from thinking about and working primarily on code, to thinking about and working primarily on other kinds of text documents: specifications, prompts, test plans. “With the right structure and documentation, these things can write very useful software” has been the theme.

I knew I’d heard that tune before.

They are writing. They are planning, they are specifying, they are reviewing plans and specs and applying their judgment to make decisions and corrections. They are revising their instructions and feedback to provide better feedback to their workers. If that’s not a description of modern knowledge work, I don’t know what is.

For 30 years, the pattern has been the same — developers build it, everyone else gets it later, polished and packaged. But this time the gap might be shorter than you think, because the work developers are doing with these tools right now isn’t primarily coding. It’s managing knowledge and managing teams.

It’s your job. And you already know how to do it.

That’s why I’ve jumped into the deep end on trying to use these tools as much like developers are using them right now, because that’s the way to understand how all of us will be using these tools in the future.

I haven’t been this excited about the future of knowledge work in decades, and if all you’re seeing and hearing is anchored to the extremes (“AI is Evil!” vs. “AI is magic!”) then you’re missing the messy middle where all of the real work that affects us all is happening.

P.S. I’m planning to share more about what I’m learning, including what is (and what isn’t) different about these tools compared with prior ones. I’m also taking a cue from Anne-Laure Le Cunff’s excellent Tiny Experiments and writing out loud about all of it. It’s been a while since I’ve done this, but some things are worth figuring out in public. This is the first post. More to come.